Dengrove Collection Writeup

Murder trial of Dr. X: Mario Jascalevich Accused of Murdering his Patients

State v. Jascalevich, 386 A.2d 466 (N.J. Super. Ct. Law Div. 1978)

It starts like a pulp novel: Myron Farber, reporter for the New York Times, gets an assignment from his editor. The paper has received a letter alleging that a medical doctor murdered 40 patients. It is June 1975. Farber traces the deaths to Riverdell Hospital—13 suspicious fatalities before or after routine surgery in 1966—and to a chief surgeon at that hospital named Mario Jascalevich.

Jascalevich was born in Buenos Aires. Riverdell hired him in 1962. Not long after, other surgeons’ patients began to die of no apparent cause. When hospital authorities inspected Jascalevich’s locker, they found 18 mostly empty bottles of curare, a potent muscle relaxant that can easily kill. Jascalevich claimed he used it to experiment on dogs. After a cursory investigation, the Bergen County prosecutor dropped the case.

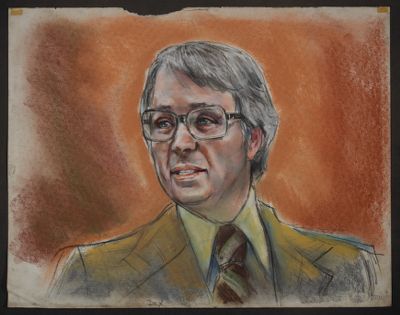

Farber published his first story on Jascalevich—calling him ‘Dr. X,’ since no guilt had been proven—in January 1976. Jascalevich was indicted that May. He chose Raymond Brown, a veteran attorney who prided himself on being “tough” and “mean,” as defense counsel. Leading the prosecution was Sybil Moses, four years out of law school.

The defense demanded all of Farber’s notes. Farber refused the order and was jailed for contempt. How are the First and Sixth Amendments to be prioritized when the two stand in conflict? Can freedom of the press inhibit the right of an accused criminal to a fair and speedy trial? The matter went all the way to the New Jersey Supreme Court.

Farber was eventually pardoned, but only once Jascalevich won an acquittal; the jury deliberated two hours, siding with Ray Brown’s summation that Farber’s withholding only proved a grand conspiracy against the doctor. Jascalevich’s medical license was revoked in 1980 for “gross malpractice or gross negligence and failure of good moral character.” He moved back to Argentina and died in 1984.