The Courtroom Sketches of Ida Libby Dengrove

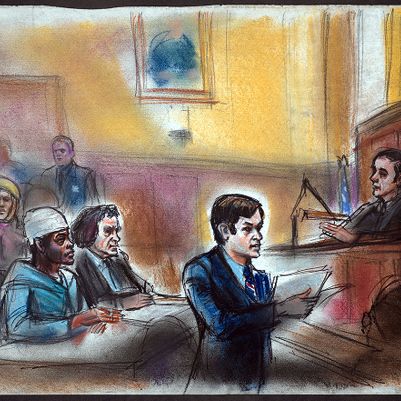

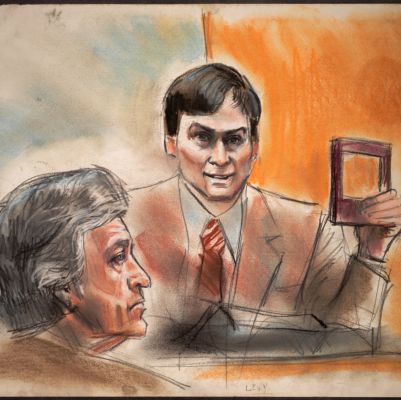

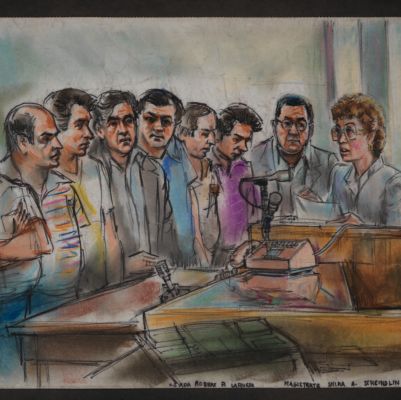

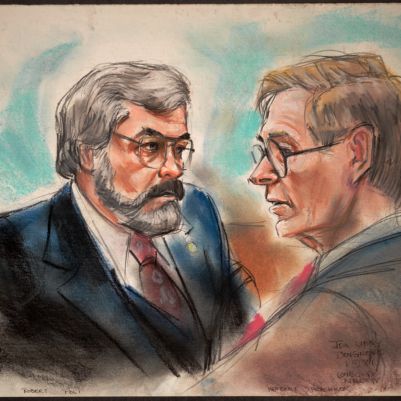

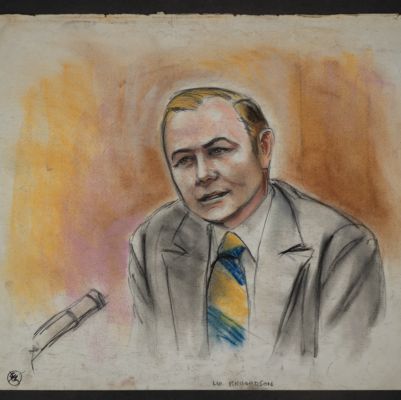

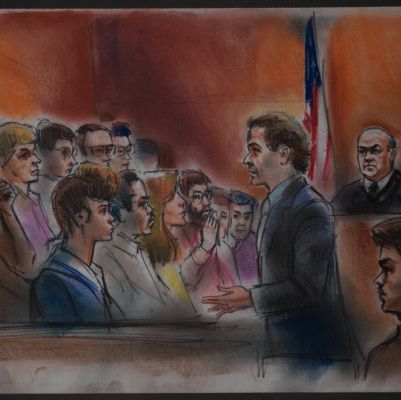

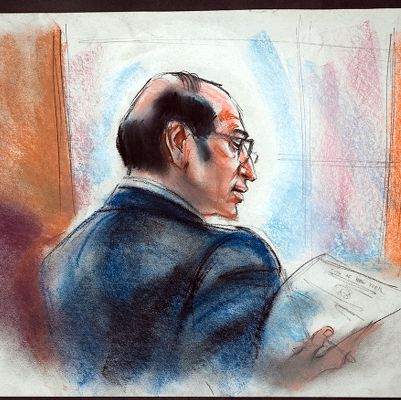

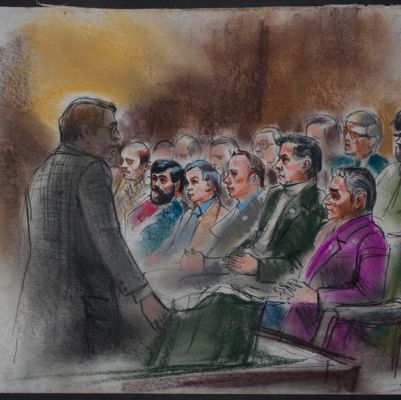

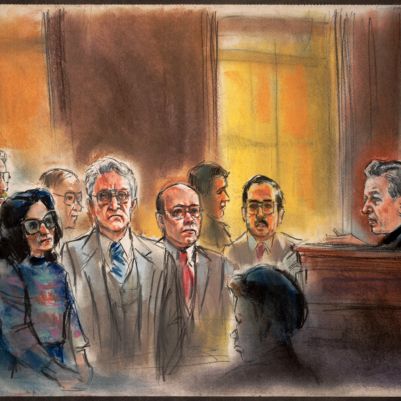

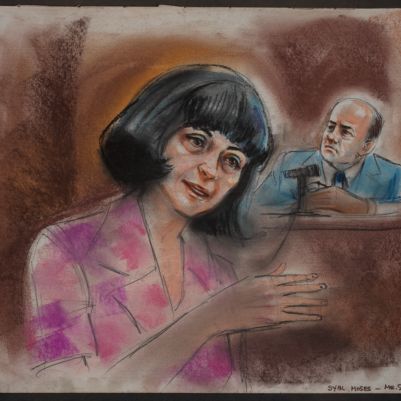

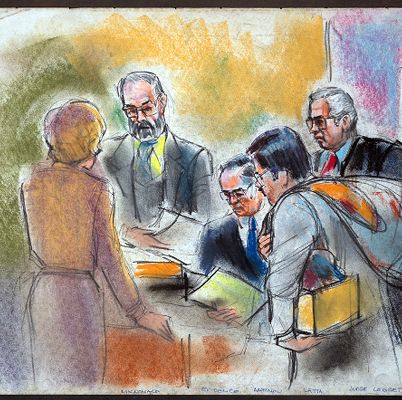

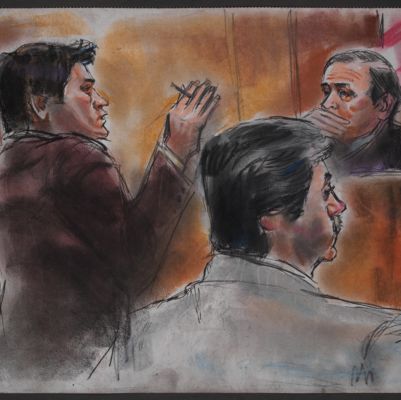

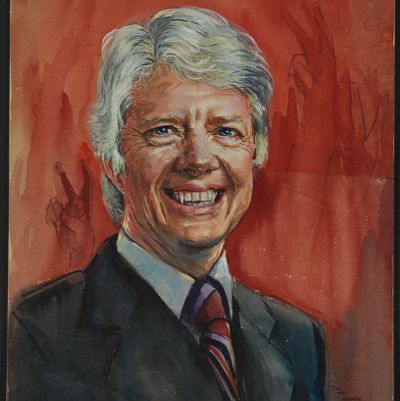

The Courtroom Sketches of Ida Libby Dengrove is a uniquely beautiful and valuable collection of courtroom sketches created by the courtroom artist from NBC from 1970 to 1980. These pictures offer an unparalled glimpse into the proceedings of Manhattan Court and contain drawings of the many characters who were part of the trials documented, including defendants, litigators, judges, and juries. Dengrove sketched many of the most famous cases of this era while also providing less spectacular but equally important images of the interworkers of New York politics, government, and law. The Law Library is delighted to preserve these important sketches and make all of them available online.

When Lois Dengrove donated her mother’s work to the University of Virginia's Arthur J. Morris School of Law Library in March 2014, it was immediately evident to the staff that what we’d acquired wasn’t just several thousand beautiful drawings, though they certainly are beautiful: witness the captain and two mates on the deck of the Argo Merchant, gazing out at ten-foot seas, the water green and blue and black and white at once, the danger so palpable you can almost hear the breakers; or stare a while at the vacant music chair, a violin and lamp-lit score waiting for a woman who met a cruel, needless fate backstage, and who would never return to play the Met ballet’s second half.

The real surprise in looking through Dengrove’s art was that it inspired questions – what became of the ship in those turbulent seas, who stole that musician from where she belonged – and they were not the types of questions typically asked of art. The questions we were asking had answers based in facts, facts waiting to be uncovered in newspaper archives, twenty- and thirty-year-old books, magazine articles, and strange crannies of the internet. And those facts were part of what made the art beautiful, meaningful, and true.

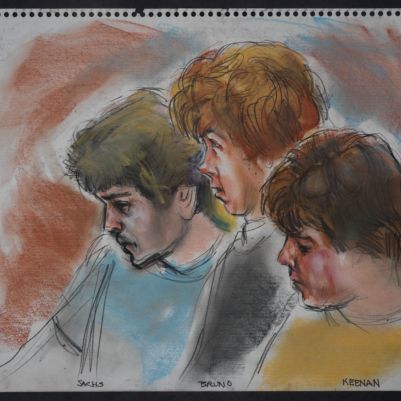

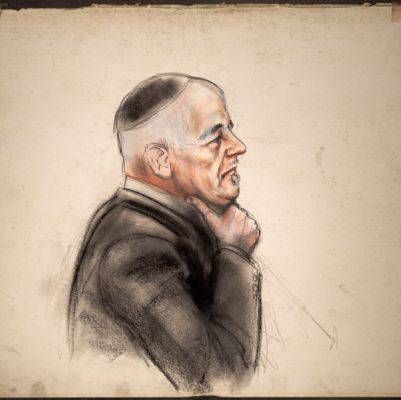

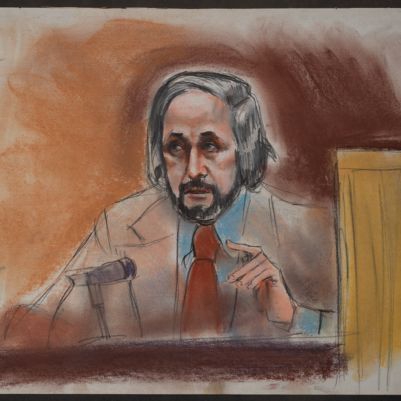

But what makes these sketches precious is that they are artifacts from an era that is all but extinct. After Bruno Hauptmann’s 1935 trial for the Lindberg kidnapping – a proceeding made chaotic by the antiquated flash equipment of 1930s cameras – courtroom photography was restricted and eventually banned. Sketch artists became the only way for the media to offer visual coverage of trials. This didn’t change until the early 90s. The media event that was the O.J. Simpson trial was unimaginable only a decade prior. This collection includes both criminal and civil trials – contested wills, Mafia dons, deportation hearings, murder, kidnapping, police brutality, and others. Our virtual gallery contains these and nearly 6,000 other sketches catalogued by topic, including 1,751 we were unable to identify or to link with a particular court case.

We welcome you to the crossroads between art and fact.

Ida Libby Leibovitz was born in 1919 and grew up drawing on the walls of her family’s Philadelphia home. She spent her summers in Atlantic City, where her mother worked, while Ida and her mirror twin, Freda, sketched portraits on the beach—one dollar for a person and two dollars for an animal, “because the animal did not stay still.” She attended Moore College of Art and Design in Philadelphia and was mentored by Dr. Albert Barnes, studying free at the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania. Both Ida and Freda traveled through Mexico and studied there with Diego Rivera in the summer of 1939; though it was Ida who won the fellowship, she took her sister with her.

Ida married Dr. Edward Dengrove shortly before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. While he served overseas as a flight surgeon with the Flying Tigers in China, Ida took a job with the USO, sketching wounded soldiers for their families back home. After the war, she and Ed raised three children. Ida remained committed to her art, teaching lessons and exhibiting at every opportunity. Freda worked as a court sketch artist for ABC News, and after Ida’s children were grown, she likewise saw court sketching as an opportunity to put her skills to wider use. When she interviewed for the position in 1972, she used her few minutes in the waiting room to draw the secretary of Bernard Schussman, news director at WNBC in New York. Schussman took one look at the portrait and hired her.

Many courts still viewed both cameras and sketch artists as degrading to the judicial process. In the early seventies, a New Jersey judge called Ida into his chambers and ruined her drawings, an action then justified by the Canons of Judicial Ethics. Dengrove and NBC fought the measure to the New Jersey Supreme Court, where a 1974 decision amended the Code of Judicial Conduct of the American Bar Association. The discretionary ban on court sketch artists was lifted.

Yoko Ono bought numerous sketches from Dengrove and invited her to her apartment several times. Jean Harris, pictured below at her trial, critiqued Ida’s sketches, asking the artist to overlook some wrinkles. Dengrove was the only journalist Harris would consent to see in prison. One of John Gotti’s henchman knocked on Dengrove’s door at 3 a.m., handing over a wad of cash for the portraits Gotti was desperate to buy.

The defining characteristic in Dengrove’s court sketches is an eerily vivid sense of the moment’s emotional impact. Families bow their heads and mourn a loss beyond imagining. Lawyers and judges squabble over rules and rulings—often with dignity, sometimes with haughtiness. Juries suffer through tedium or horror, depending on the day. And men and women on trial for unspeakable acts gaze into an unknown other world, where they are no doubt the heroes of their own stories.

“I sincerely tried to do my best on every assignment,” Dengrove wrote. “I saw and experienced so much, and it was the most exciting period of my life.” In a time when cameras were barred from courtrooms, the American public relied on sketch artists to be their eyes inside the judicial system. Nobody gave us eyes quite like Ida Libby Dengrove. Even after the onset of Alzheimer’s, when her daughter, Lois, brought her to California, Dengrove drew and painted every day—as if the need to see the world around her and share that view with others burned brighter than the dying of the light. She was drawing the day she passed away—April 13, 2005—from complications of the disease, leaving behind more than six thousand drawings that span nearly three decades of life and death in our courts. This exhibit is in tribute to one woman who did a great justice to art, by making an art out of justice.

In early March 2014, the Arthur J. Morris Law Library received nearly 6,000 courtroom sketches from the family of Ida Libby Dengrove. This collection, remarkable in its scope and artistry, offered an unprecedented window into American courtroom proceedings. Upon receiving this generous gift, the library’s special collections staff preserved, catalogued, and described all of the sketches. In addition, every sketch was digitized. These high-resolution digital images are all available on this site. Our staff accomplished the entire project from receiving the sketches to their final preservation and display in five months.

The collection of sketches arrived at the library in one large crate, with 15 smaller crates containing loosely organized envelopes containing the sketches. To preserve them, each individual sketch received a protective paper sleeve and was then stored in an acid-free folder. These folders were placed in a total of 60 archival preservation boxes, amounting to 20 linear feet of storage.

Gleaning any bits of information from each, our staff used the available information about the subjects and trials to research and tag every one of Dengrove’s sketches. Then, for the larger or more famous trials, personalities, and subjects, we more extensively researched and wrote up longer descriptive pieces, what we called "write-ups.”

Once preserved and described, each sketch was digitized using our 60 MP Hasselblad H4D digital camera. The preservation-quality digital originals were then preserved, and derivative web-deliverable JPGs were created. Then, all of the information created during the cataloging and researching process was combined with these images and entered into this Drupal-based website.

Taylor Fitchett – Library Director

Loren Moulds – Digital Collections Librarian

Cecilia Brown – Library Archivist

Gina Wohlsdorf – Research

Michael Srstka – Cataloging

Oleksandra Skulinets – Digitization & Database Management

Philip Herrington – Research & Copy Editing