Dengrove Collection Writeup

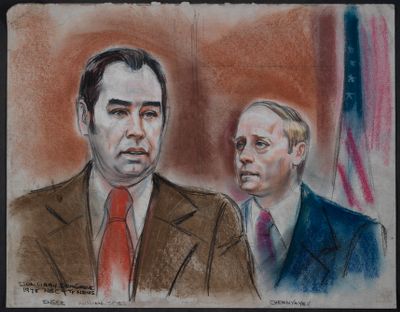

Chernyayev and Enger

The Cold War sometimes felt like a high-stakes chess game, only real people played the pieces. On May 20, 1978, police arrested three Soviet citizens in Woodbridge, New Jersey. One of the men had diplomatic immunity and was released. The other two – Rudolf Chernyayev and Valdik Enger, employees of the UN Secretariat – were seized and held on espionage charges. They possessed materials relating to an underwater warfare project being conducted by the US Navy.

The Soviet Union responded to the duo’s arrest on June 12 by charging Francis Crawford – an American businessman in Moscow – with currency violations. Crawford’s five-year suspended sentence was widely seen as a bargaining tactic, and indeed, after their conviction on October 30, Chernyayev and Enger were released pending appeal into the custody of a Soviet ambassador. Officials arranged a trade – the two spies for five Soviet dissidents. This was the first time Soviet citizens were exchanged for other Soviet citizens.

“I thank my Lord that I am free,” said Georgi Vins, one of the dissidents, reading from a statement after arriving – gaunt and pale, with his head shaved GULAG-short – in the US. “I thank President Carter . . . and all the people of good will who have been interceding for the persecuted Christians in the Soviet Union.”

Just before boarding the flight that would take him home, a well-fed, healthy Valdik Enger turned to the US district attorney who prosecuted him and said, cavalierly, “I would have enjoyed meeting you under different circumstances.”