Dengrove Collection Writeup

Luis Bonilla

A spate of brutal subway slayings committed by youth offenders drove the state of New York to desperate measures in the summer of 1978. That July, the State Legislature enacted a measure declaring that juveniles – at least thirteen years of age, but under sixteen – stand trial as adults in criminal court for serious offenses, rather than as minors in family court. The law took effect in September.

On October 21, Israel Vasquez, age 17, was in a Bronx apartment building when Luis Bonilla, age 13, demanded Vasquez’s portable radio. Vasquez refused to hand it over. Bonilla shot him twice in the back with a .22-caliber pistol.

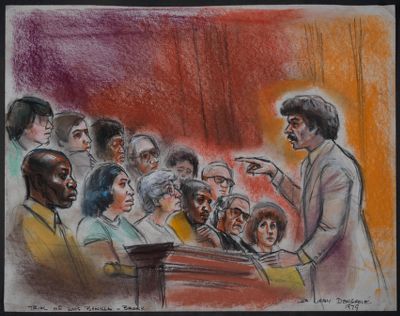

Bonilla had turned 14 by the time of the trial, which took place in criminal court. A guilty verdict carried a maximum sentence of life with the possibility of parole in 5 years, but the jury, after deliberating 15 hours, convicted Bonilla not of murder, but of manslaughter.

Manslaughter was not under the auspices of the new juvenile offender law. Bonilla was remanded to family court, where he received a sentence of three years. Only for the first year would he be in supervised custody.

The Bonilla case inflamed rather than resolved the debate surrounding juvenile penal reform: critics of the new legislation decried children’s presence in adult courtrooms; defenders countered that family court was designed for the petty mischief of wayward minors and that the penalties available to those proceedings were insufficient to deter more serious crimes.