Dengrove Collection Writeup

NYPD Officer Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity for Shooting Ninth-Grader

In re Torsney, 394 N.E.2d 262 (N.Y. 1979)

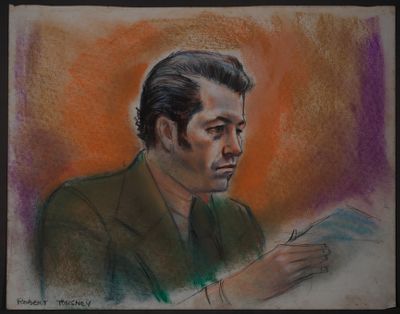

Robert Torsney had been a by-the-book cop for eight years as of Thanksgiving 1976, when he and fellow officers responded to a call in the Cypress Hills housing project. Finding the situation resolved when they arrived, Torsney left the apartment building and walked up to ninth-grader Randolph Evans. The two had a brief conversation before Torsney shot the youth point-blank in the head.

Typically, a shooting by an on-duty police officer results in a suspension while the grand jury investigates. But Torsney’s fellow officers arrested him instead. He was released on bail, a fact that caused enormous racial tension in the city: Evans was black; Torsney was white.

Torsney underwent psychiatric evaluation, and a year later, when on trial for second-degree murder, the officer pleaded insanity. On the stand, he claimed the victim had reached for “a silver object.” No one corroborated Torsney’s account. A psychiatrist for the defense testified Torsney suffered from epilepsy and that he was mid-seizure when he fired his weapon.

The all-white jury ruled Torsney not guilty by reason of insanity. He was released from psychiatric care a year and a half later, his doctor stating, “We find he suffers from no mental disease since he has been with us.” The Appellate Court, attempting to block the order, was met by his counsel’s insistence that mental health institutions bore no responsibility for a miscarriage of justice.

Torsney filed for a $15,000-a-year disability pension but was denied after being discharged from the police department.